Date reviewed > 2022 > Apr

Sections > Book Review | Yoga | Peoplescape

Krishnamacharya Blogs

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya Blogs

Yoga Book Reviews

YOGA Book Reviews

FREE online books

BooksFree.org | Project Gutenberg | Open Library | ManyBooks | Free-eBooks.net | Bookboon | Smashwords | PDFBooksWorld | PDF Drive | Google Books

Apr 7, 2022

Apr 7, 2022

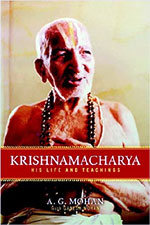

Krishnamacharya: his Life and Teachings

November 18, 1888 - February 28, 1989 (age 101)

Author: A.G. Mohan

A.G. Mohan's Website: www.svastha.net

ISBN-10: 159030800X

ISBN-13: 9781590308004

Genre: Yoga

Publisher: Shambhala Publications

Publication date: July 13, 2010

Rating:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (5 out of 5 stars)

(5 out of 5 stars)

A.G. Mohan

A.G. Mohan

This book comes from Krishnamacharya's direct lineage - his student of 18 years (1971 to 1989), A.G. Mohan (born 1945). Mohan was 26 years old then while Krishnamacharya was already 83. By profession, Mohan was an engineer. When he met Krishnamacharya for the first time, there was something in him that was triggered - he knew he found his guru.

Here, Mohan clarifies ambiguities and explains the legendary stories surrounding this great master. The book is focused on the master's life and teaching about Asana, Pranayama, Kriyas, Yoga Therapy and the Mind. Not much has been written about Krishnamacharya's early life and since the master tried to recollect events decades in the past, there are inconsistencies and different versions. Writing this book was done by A.G. Mohan's son, Ganesh Mohan, as his father was narrating the story.

I. Overview of the Life of Krishnamacharya

As a Child (age 0-12)

Krishnamacharya was born in Karnataka in 1888 and grew up in the Vaishnavite tradition (devotees of the god, Vishnu, aka Narayana). As a child, Krishnamacharya was already learned in the Vedas (ancient body of knowledge that forms the basis of what is now known as Hinduism), as taught by his father. By age 12, he was already versed in sanskrit, vedanta (an important system of Vedic philosophy), asana (physical postures in yoga) and pranayama (regulated breathing).

Varanasi (1906, age 18)

Krishnamacharya traveled to Varanasi to further his studies, where he earned a scholarship which helped augment his expenses. He also earned a Yoga Degree in the city of Patna. Krishnamacharya's sharp intellect and devotion to his pursuits earned him the trust and assistance of a few higher-ups who entrusted him with the tutoring of their immediate family members - either in yoga or academics.

Off to the Himalayas

In Varanasi, Krishnamacharya met the school principal at that time, Ganganath

Jha, who advised him to seek Ramamohana Brahmachari, a yoga master who lived in a cave in the Himalayas, if he wanted to deepen his yoga practice. Jha made arrangements for Krishnamacharya to be assisted by the viceroy of Simla on his journey to the 'Land of Snows'. The viceroy requested Krishnamacharya to come back to Simla 3 months a year to teach him yoga. This was after Krishnamacharya cured him of diabetes through yoga. Krishnamacharya walked 200 miles in the Himalayas at altitudes over 15,000 feet, in 3 weeks, until he reached the hermitage of Ramamohana Brahmachari near Lake Manasarovar.

At the Hermitage of Ramamohana Brahmachari in Tibet (1910-1918, age 22-30)

Krishnamacharya was warmly received by the guru, his wife and 3 children. In the 7 1/2 years he stayed there, he learned the Yoga Sutras, Samkhya philosophy, asana and pranayama. Towards the later end, he began learning practical applications of yoga therapy. Upon leaving, Krishnamacharya's guru dakshina (payment to the teacher for all the teachings) was to continue teaching yoga and have his students spread the practice. (note: from another source, I read that aside from teaching yoga, the other guru dakshina was to look for the Yoga Korunta book [which Krishnamacharya found at the University of Calcutta, but later on devoured by ants], and to marry and have a family [so he has to be a householder and cannot be a monk]. An unseen ramification of teaching yoga means that Krishnamacharya can only go so deep in his practice because part of his time has to be devoted to teaching. This is the reason why some yoga adepts do not teach - they would rather use all their time to deepen their practice.)

Back to Varanasi (1918, age 30)

After Tibet, Krishnamacharya returned to Varanasi to further his studies. He earned accolades for his treatise that brought clarity on how a Vedic ritual was to be performed. He continued to travel, participating in debates and discussions, and earning such degrees as Veda Kesari and Nyaya Ratna from centers in North India. He was also honored for his prowess in debate and his knowledge as a scholar by the maharajas of Baroda and Kasi.

Maharaja of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wadiyar (1926-1946, age 38-58)

The Maharaja of Mysore met Krishnamacharya in Varanasi and was so impressed by his knowledge and dedication that the maharaja invited him to teach yoga in Mysore. A yoga school was founded there by the maharaja for Krishnamacharya. When India became independent from the British, the maharaja lost power and the school was closed.

Yoga Makaranda (1934, age 46)

Krishnamacharya authored his first book, Yoga Makaranda, which was published by Mysore University.

Chennai (~1946, age 58)

Krishnamacharya settled in Chennai after the closure of the yoga school in Mysore. Here, he continued to teach yoga. He was already 58 with wife, 3 sons and 3 daughters. He would stay here until his passing.

II. Meeting the Master and Early Studies (1971–1973)

A.G. Mohan and Krishnamacharya Meeting (1971, age 82)

This was the first time Mohan met Krishnamacharya - in a lecture. At first glance, Mohan was spellbound. Krishnamacharya's subtle radiance and authority left an indelible mark on his mind. He knew he found his guru - the one who can deepen his spiritual and philosophical aspirations. To ease his way into Krishnamacharya, Mohan first attended yoga classes from Krishnamacharya's son, Desikachar. He would also concurrently attend the group lectures conducted by Krishnamacharya. It wasn't until 1973 when Mohan was formally accepted by Krishnamacharya as a student, studying Prasnopanishad (the last Vedic chapter, dealing with prana) and yoga as well (when Desikachar had to leave). More than just a yoga instructor, Krishnamacharya was a spiritual teacher and was accorded such deference.

Krishnamacharya was a no-nonsense, prompt, disciplined teacher, keenly observant and sensitive to nuances. Payment was left at the foot of the altar...never given directly to Krishnamacharya. The amount of payment depended on the student - his means and what the teaching is worth to him - but this was unspoken.

In the 18 years that Mohan was a student, he had accumulated 5000 pages of notes from the classes. Even if unclear during that time, Mohan would refrain from asking questions, knowing that in time, he will develop an understanding to all of them.

III. Asana

The Mind

The mind darts out uncontrollably in any direction. It has no form, no shape and ungraspable. The goal of yoga is to control this mind and turn it into a sharply focused mechanism - according to the Sutra of Patanjali.

Hatha Yoga

Hatha Yoga, aka Raja Yoga, according to Patanjali (Yoga Sutras) and Yogi Svatmarama (Hatha Yoga Pradipika) makes the body strong but also the mind. With hatha yoga, the body is strong and resilient from disease.

Breathing

Krishnamacharya emphasizes slow ujjayi breathing, constricting the vocal cords so you feel the passage of air...as a smooth rubbing on the throat. Awareness is not confined to the mechanical breath, but the internal sensation of the flow of breath...the flow of prana.

32 Variations to a Headstand

When Krishnamacharya talked about 32 variations to a headstand, Mohan expressed a doubtful look which didn't go unnoticed to Krishnamacharya's eyes. Standing up to the occasion, at 85 years old, Krishnamacharya performed all 32 variations of the headstand to the astonishment of Mohan.

Practice at Home or Class is Ended

The weekly classes with Krishnamacharya were supposed to be supplemented by home practice. When Krishnamacharya noticed that there was no improvement in Mohan's practice compared to the past week, he questioned if Mohan failed to do his home practice. That being established, Krishnamacharya ended the class right there and then. This served 2 purposes: 1) to underscore that home practice is important and 2) to not proceed with a challenging practice if the student is not ready (which in this case was a shoulder stand). This also displayed Krishnamacharya's sharp sense of observation.

Asymmetric Asanas

Krishnamacharya is keen on using asymmetrical asanas to correct an imbalance. When Mohan's right leg was swaying on a headstand, Krishnamacharya realized it was because Mohan was using his right leg to shift gears on his motorcycle while his left leg was free. To correct this imbalance, he made Mohan do an ardha-salabhasana - a locust where only one leg is lifted up. This compensates for the overworked leg and thus restores balance.

Headstand

Krishnamacharya was particular about the headstand. Yes, it is an asana but it performs a special function as well that elevates it to a mudra. The breathing has to be extra slow, extra deep with extra focused awareness. When done correctly, progression can include a bandha that prepares the body for a particular kind of meditation. Ideally, the headstand should be done at 2 full breaths/minute for the next 12 minutes.

Improper headstand can result in numbing fingers, hand tremors or speech impediment. The student needs to be strong in the practice and ready for a headstand. It's equally important for the teacher to know what he is doing.

How Many Asanas?

While Patanjali only mentioned padmasana as an asana in his yoga sutras, Krishnamacharya claims that his teacher knew 7,000 asanas, from which he learned 700. He added that there were 84,000 at the time of Sankara, 64,000 at the time of Ramanuja and 24,000 at the time of Madhva. (This puts asana in perspective as I was once accused by a yoga teacher that my yoga wasn't yoga because my asanas were 'not' traditional yoga asanas.)

A Comprehensive Asana Class

Krishnamacharya's asana classes are not limited to adjustment and proper form. He included such information as the benefits of an asana, recommendations for linking the breath to the asana, the vinyasa krama, contraindications, classical references and derivations from ancient sources (both well known and obscure), common variations, useful modifications and therapeutic applications, mental focus during the practice, suggestions for the practice of bandhas, etc.

Vinyasa Sequences

Krishnamacharya is the first of the yoga masters to implement the vinyasa - weaving the asanas together with the breath so it becomes a flowing movement. One movement, one breath, synchronized into a flow. Still, there are asanas best held for a few breaths to maximize their benefits.

Mental Focus and Attitude

Krishnamacharya would often say, "no mental control, no yoga". Awareness has to be present at all times, otherwise the asana is reduced to a mere physical exercise. Moreover, generating the right feeling or attitude is essential. Example - in Warrior Pose, generate the feeling that when you look down, you are above worldly concerns. Or feel that you are neither in the past nor future....you are present.

Bhagiratasana / Tree Pose / Vrkshasana

Perhaps it is only Krishnamacharya who calls the Tree Pose, Bhagiratasana. The legend speaks for itself. To revive his forefathers from their ashen existence back to human form, Bhagirata had to cause the Ganges River to flow to earth and wash away the ashes. For this, he had to plead to Brahma, ask permission from Ganges, implore Shiva and plead with the sage Agastya. Altogether, it took Bhagirata a few thousand years of focused meditation on one leg. So by calling the Tree Pose the Bhagiratasana, you internalize the unshakable mental resolve of Bhagirata in his meditation.

Anjali Mudra

Anjali is different from the Namaste gesture although both look almost identical. The Anjali resembles a flower bud, about to open, likening the opening of the heart for spiritual awakening. This also reminds us to live with humility instead of boosting our ego.

Classical Yoga Texts: Pros and Cons

There are classical yoga texts used as reference in today's practice of yoga that presents contrasting focus. Some focus more on and mind, while some only on physical postures.

- Yoga Sutras - codified by Patanjali. It has 195 sutras with only one line referring to asana - a seated position that is comfortable and steady to keep the spine straight and unrestrain the stomach and lungs. Most of it focuses on the mind.

Yoga Sutras: An introduction by Alan Goode

Modern Yoga Studies

This document is a compilation of background information on yoga drawn from Light on Yoga Sutras of Patanjali by BKS Iyengar, A History of Yoga by Vivian Worthington, (now out of print) and Barbara Stoller Miller, Yoga

The Buddha came into contact with this movement, becoming as one of them, a wandering mendicant beggar,first absorbing the teachings, trying to find their relevance for him, and eventually putting out his own distinctive contribution. Yoga practice at that time, reduced to its barest essentials, comprised austerity,meditation and non-violence. In his first and most famous utterance, the sermon at Benares, also called the Sermon of the Turning of the Wheel of the Dharma, the Buddha himself referred to a long line of teachers or Rishis who had gone before, and whose line of teaching and practice he was continuing. At a time of great spiritual awakening, between 600 and 400 BC two of the greatest exponents of yoga formed movements that were to become great religions. These were Jainism and Buddhism. Yoga practice continues as part and parcel of these faiths, as it does for modern Hinduism. Yoga went to China and Japan along with Buddhism but became more distinctive as the Chan in China, and the Zen sects in Japan. In the Moslem world it worked its leaven through Sufis, and is now doing the same in Christianity.The reason why Yoga survives, and will continue to live, is that it is the repository of something basic in the human soul and psyche.’

Yoga as Philosophy: The Six Systems

History of Yoga

‘After Patanjali had systematised yoga, or to be more precise raja yoga, in his justly celebrated Sutras the subject became understandable in an intellectual way. Previously it had merely been looked on as a system of self-development, an ascetic discipline which shunned all intellectual argument and maintained that the stage of moksa, liberation, which it sought, was beyond mind and therefore beyond philosophy. This is still the view of true yogis. In keeping with the Sramanic tradition the ultimate depository of the yoga system is to be found in the personal lives and examples of its devotees. No amount of discussion or formulation will get beyond that essential basis. However, the academic world loves to categorise and so attempted to fit Patanjali's Sutras into the intellectual framework of Indian life. This was probably done against the wishes of practising yogis.There are no records to tell us one way or the other. It fitted yoga into this intellectual straitjacket by coupling it with its illustrious contemporary, samkhya. The aims of yoga and Samkhya are the same. The methods of achieving those aims are not in conflict. They are complementary in that yoga is primarily practical, while Samkya is essentially intellectual. Moreover Samkhya possessed a most attractive cosmology and psychology, which yoga is able to subscribe to wholeheartedly . Thus yoga became a subject of study in the universities of India along with other philosophies, and about the year AD 200 it was fitted into the scheme of the Six Systems of Philosophy, a position held to this day, although largely irrelevant to the true life and purpose of yoga - unlike the other five which sit fairly comfortably in the academic mould. These Six Systems are not really complete in themselves, but are all complementary to each other, so are looked on as six parts of a complete Indian system. The six grew out of sixty-two systems. They provide ametaphysics, a religion, an explanation of ultimate reality, and a means of salvation. They tend to be bracketed together in pairs. The oldest are Yoga and Samkhya, the next being Vaisesika and Nyaya, and the final pair Purva Mimamsa and Vedanta. They are often referred to as Darsanas or points of view. Each of them propounded their systems in the form of short sutras whose elucidation requires lengthy commentaries. All seem to stand at the end of a long period of discussion and disputation (or practice in thecase of yoga), rather than as initiators of anything new. The six were formulated from the about the year AD200 and take us right up to the present time as far as Indian philosophical speculation is concerned.’‘References to asanas (postures and exercises) are found in yoga literature right back to the Upanishads. At that time the asanas were for purposes of meditation. The body was to be placed in a suitable seated posture so that the aspirant could meditate with a straight spine, and with lungs and stomach not restricted. In such a position the body could be forgotten and rhythmic breathing practised. The classic position has always been Padmasana, or Lotus Seat.

Developing Siddhis

When sitting not just for quiet meditation, but for development of siddhis or psychic powers, it was found that some other seated postures were more conducive to such activities. The hands were placed in different ways, from which developed a range of hand gestures known as mudras. The number of breathing exercises increased. A range of cleansing practices came into being known as kriyas, and several body locks known as bandhas, similar to mudras but with a different purpose. This array of physical practices was considered entirely secondary and subservient to the main practice, which was sitting for meditation with the object of eventually achieving samadhi. These practices were not even mentioned during the classical period, except to say, as in Patanjali and in the Bhagavad Gita that a comfortable seated position was necessary for effective meditation. In the tantric period, however, when attempts were being made to develop the siddhis, more active exercises began to be employed. It was also noticed that the general health of yoga practitioners could often be greatly improved by the practice of certain asanas. It began to be apparent that the purely physical aspect of yoga had its own considerable value.Nath yogis of Gorakhpur

The Nath yogis of north India took up this aspect of the art, and widened its basis considerably. They flourished from the tenth to the twelfth centuries in the area round Gorakhpur near Nepal. The founder of the Nath yoga sect, also known as Natha-Siddhis, was Goruknath. The Gurkhas derive from this area. From all accounts the Nath yogis were extremely vigorous, being devoted to physical fitness. They were much travelled and their way of life was very austere. Being often in situations of great danger they became adept at various martial arts. The fighting traditions of the Gurkhas lend credence to this fact. Claims have also been made that they carried knowledge of these practices into China and were thus instrumental in laying the foundations of the Chinese martial arts such as judo and karate. These claims have not yet been substantiated. As the Nath yogis were also known as Natha siddhis it is obvious that they were likewise renowned for their psychic powers. They lived quite close to Tibet, at a time when Milarepa had given a further impetus to such experimentation in that country. In pursuance of the siddhis the Natha yogis developed a range of asanas, kriyas, mudras, bandhas and pranayamas. Their yoga became distinguished from the other forms by taking the name hatha yoga. Hatha is a compound word. 'Ha' means sun, and 'the' means moon. This is a reference to pranayama. The right nostril is positive, and represents the sun. The left is negative, and represents the moon. Both must be brought into balance if our nature is to be balanced. Because the nadis ida, pingala and sushumna form a triple knot at the nose, correct breathing exercises will activate the chakras, and through them the whole internal environment of the body. So, although hatha refers only to the breath, hatha yoga has come to mean the whole range of yoga physical exercises. The Nath yogis were social reformers. They tried to break the caste system, and treated women and outcastes as equals. For their pains they were themselves relegated to a lower caste by the Brahmin establishment. This Natha caste still survives as a very small group living in the Vindhya range of mountains in north India. Today they are largely unaware of the revolution wrought by their forebears. The Nath yogis also attempted to unite Hindus and Buddhists in their region - a fruitless task, but a worthy effort. They appear to have been neither Buddhist nor Hindu themselves; perhaps they were both. Goruknath and his followers left notes and instructions on the various asanas, mudras, pranayamas, bandhas and kriyas, but not in the form of a complete text. These fragments were gathered together by Svatmarama Swami and published in the fifteenth century as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.’What knowledge does it deal with?

‘Patanjali’s yoga offers a set of powerful techniques for countering the tyranny of mental chaos and moral confusion. Personal freedom is the concern normally associated with the private sphere, and morality with the public sphere. But they are inseparable. In the ancient Indian hierarchy of values, a concern with ultimate spiritual freedom is dominant. And yet the discipline that is required to achieve freedom is rooted in moral behaviour, according to Patanjali. Even though proper moral action in the world is not the goal of yoga, a great vow to live by the universal principles of non violence truthfulness, avoidance of stealing, celibacy and poverty is specified as a precondition for further yogic practice. The cultivation of friendship, compassion, joy and impartiality towards all creatures, a central formula of Buddhist ethics, is also deemed effacious for achieving the absolute tranquility of yoga. The antiworldly isolation prescribed for certain stages of yoga is not the ultimate yogic state. Periods of solitude are necessary, but one need not renounce the world forever to practice yoga.’Yoga as Religion

‘The essential assumption underlying yogic practice is that the true state of the human spirit is freedom which has been lost through misidentification of ones place in a phenomenal world of ceaseless change. This is the root of human suffering. Paradoxically, in yoga the freedom of spiritual integrity occurs in the act of the discipline itself, which is ultimately rendered superfluous by the reality its practice discloses.’Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

Patanjali's Yoga Sutras deals with our relationship to the world and the way our senses, thought and past experiences lead us inextricably towards pain within ourselves. Yoga is not so much a system of belief as a set of practices which allow us to see the influence and relationship of thought, experience and senses. A study of consciousness.Padas

The yoga sutra in 4 chapters (Padas) outline the practices, benefits or attainment’s, and the ends of yoga. This is done in aphorisms or sutra - short terse statements which state the essence. This was done as yoga being an oral tradition was learnt by chanting the sutras after which the teacher would discuss the meaning. This has lead to the various schools of thought and divergence in the practices.Samadhi pada - on contemplation

Sadana pada - on practice

Vibhuti Pada - on properties and powers

Kaivalya pada - on emancipation and freedomChapters 1 and 2 are those most commonly studied. The astanga yoga limbs are the central tenet of the sutra and outline the practices and progression of yoga but before we start on these we must consider the observations yoga makes of our existance.

What is yoga – its aim?

‘Yoga is most concerned with the effects of our actions within us, not the effects of our actions on others. Stealing is not a problem of morality but a problem because it generates more desire, a desire which can never be fulfilled.’The essential assumption underlying yogic practice is that the true state of the human spirit is freedom which has been lost through misidentification of ones place in a phenomenal world of ceaseless change. This is the root of human suffering. Paradoxically, in yoga the freedom of spiritual integrity occurs in the act of the discipline itself, which is ultimately rendered superfluous by the reality its practice discloses.’

The aim of yoga is to see clearly - to see the nature of reality. We experience the world through the senses. The senses become clouded and unreliable - this happens in 2 ways - the senses become clouded through desire and aversion, and Samskaras. Yoga is the cleansing of that lens of the senses through which we experience. We will consider these 2 effects.

Senses

One of the main concepts underpinning yoga is drawn from the classification of everything into two categories –nature and soul, and the effect of a busy life on our ability to know ourselves. We live in a world of illusion where things are not as they first appear. Over stimulation draws the senses outwards - we live to fulfill our desires. We attribute our happiness to objects outside ourselves. We are so full there is no chance to know ourselves or hear the small quite voice of God within. Everything – all experience and all material objects come under the two classifications:Prakrti/Nature - Everything that exists in the world, including the body, the senses, and even thought.

Purusa/Soul - That unchanging place within each of us that is untouched by the world around us.

Characteristics of Purusa

‘Purusa, the seer or the soul, is absolute pure knowledge. Unlike nature (prakrti), which is subject to change, purusa is eternal and unchanging. Free from the qualities of nature, it is an absolute knower of everything. The seer is beyond words, and indescribable. It is the intelligence, one of natures sheaths, which enmeshes the seer in the playground of nature and influences and contaminates its purity. As a mirror, when covered with dust, cannot reflect clearly, so the seer, though pure, cannot reflect clearly if the intelligence is clouded. The aspirant who follows the eightfold path of yoga develops discriminitive understanding, viveka, and learns to use the playground of nature to clear the intelligence and experience the seer’Samskaras - Past impressions or imprints

‘In order to penetrate the logic of Patanjali’s method, it seems crucial to grasp his analysis of how Purusa becomes bound to material mature through the workings of thought (Citta) and the accumulation of subliminal memory traces or impressions (Samskaras). The central notion here is that any mental or physical act leaves behind traces that can subtly influence a person's thought, character, and moral behaviour. The store of memory is composed of subliminal impressions (Samskaras) and memory traces (vasana), which are the residue of experience that clings to an individual throughout life and, in the Indian view, from death to rebirth. The relation between the turnings of thought - citta vrtti and memory is basic to Patanjali’s epistemology. When thought passes from one modification into another, the former state is not lost but rather is preserved in memory as a subliminal impression or memory trace. Thus, thought is always generating memories, and these memories are a store of potential thoughts, available to be actualised into new turnings of thought. The very act of thinking not only generates but preserves memories, like roots of a tuber that spread underground and produce fresh tubers which blosom in season.’Vrttis (endless cycles of fluctuations)

‘These endless cycles of fluctuations are known as Vrttis: changes, movements, functions, operations, or conditions of action or conduct in the consciousness. Vrttis are thought waves, part of the brain, mind and consciousness as waves are part of the sea. Thought is a mental vibration based on past experiences. It is a product of inner mental activity, a process of thinking. This process consciously applies the intellect to analyse thoughts arising from the seat of the mental body through the remembrance of past experiences. Thoughts create disturbances. By analysing them one develops discriminative power and gains serenity. When consciousness is in a serene state, its interior components, intelligence, mind, ego and the feeling of I also experience tranquility. At that point, there is no room for thought waves to arise either in the mind or in the consciousness. Stillness and silence are experienced, poise and peace set in and one becomes cultured. One’s thoughts, words and deeds develop purity, and begin to flow in a divine stream.’Why practice and detachment?

‘Freedom, that is to say direct experience of Samadhi, can be attained only by disciplined conduct and renunciation of sensual desires and appetites. This is brought about by adherence to the twin pillars of yoga, abhyasa and vairagya. Abhyasa (practice) is the art of learning that which has to be learned through the cultivation of disciplined action. This involves long, zealous, calm, and persevering effort. Vairagya (detachment or renunciation) is the art of avoiding that which should be avoided. Both require a positive and virtuous approach. Practice is a generative force of transformation or progress in yoga, but if undertaken alone it produces an unbridled energy which is thrown outwards to the material world as if by centrifugal force. Renunciation acts to sheer of this energetic outburst, protecting the practitioner from entanglement with sense objects and redirecting the energies centripetally towards the core of being.’‘Abhyasa (practice) dedicated, unswerving, constant, and vigilant search into a chosen subject, pursued against all odds in the face of repeated failures, for indefinitely long periods of time. Vairagya is the cultivation of freedom from passion, abstention from worldly desires and appetites, discrimination between the real and unreal. It is the act of giving up all sensuous delights. Abhyasa builds confidence and refinement in the processof culturing the consciousness, whereas Vairagya is the elimination of whatever hinders progress and refinement. Proficiency in Vairagya develops the ability to free oneself from the fruits of action’.

Practice implies a certain methodology, involving effort. It has to be followed uninteruptedly for a long time, with firm resolve, application, attention and devotion, to create a stable foundation for the training of the mind, intelligence, ego and consciousness. Renunciation is discriminative discernment. It is the art of learning to be free from craving, both for worldly pleasures and for heavenly eminence. It is training the mind to be unmoved by desire and passion. One must learn to renounce objects and ideas which disturb and hinder one’s daily practices. Then one has to cultivate non-attachment to the fruits of one’s labors. If abhyasa and vairagya are assiduously observed, restraint of the mind becomes possible much more quickly. Then, one may explore what is beyond the mind, and taste the nectar of immortality, soul realisation. Temptations neither daunt nor haunt one who has this intensity of heart in practice and renunciation. If practice is slowed down, then the search for soul realisation becomes clogged and bound in the wheel oftime.’

Ashtanga Yoga

Patanjali outlines the 8 fold path of Ashtanga yoga for the first time- YAMA . Ethical Disciplines. These include Non-violence, Truthfulness, Not stealing, Not misusing sex, Not coveting.

- NIYAMA . Individual Disciplines. Purity, Contentment, Ardour or Austerity, Self study, Surrender to God.

- ASANA . Cleansing and strengthening the body. Asanas are not just exercises but they strengthen every muscle, joint and gland in the body bringing lightness and stability. The real importance of the Asanas is the way they train and discipline the mind. These first three limbs form the outward quest (bahiranga Sadhana), helping to control the Yogi's emotions and passions and keep one in harmony with Humanity. Asanas keep the body healthy and strong and inharmony with nature.

- PRANAYAMA . Breathing techniques. where the Yogi learns to observe and channel the breath. Directing it's energy

- PRATYAHARA. Sense withdrawal. Where the senses are withdrawn from outside stimulus and turnedinwards to observe the core of the being.These two limbs form the second stage, the inward quest (Antaranga Sadhana ). When the body has beenmade light and strong and the Yogi has gained control of the outer form, the Yogi moves to observe thenuances of the inner being. To learn stillness and inquiry

- DHARANA . Concentration on an object

- DHYANA. Contemplation or Meditation

- SAMADHI . To become one with the object of Meditation.These last three take the Yogi to the innermost recesses of the Soul and are called Antaratma Sadhana, thequest of the soul

- Yoga Yajnavalkya - this text predates Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP) and is given more weight by Krishnamacharya. In fact, HYP borrowed some texts verbatim from Yoga Yajnakalkya. It does not mention any kriya (cleansing) but talks a lot about pranayama

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika - by Yogi Svatmarama, focuses more on asanas and by far the default reference for yoga practice today

- Gheranda Samhita - by the great sage Gheranda. It's a 'how to' yoga manual consisting of 7 Limbs (not 8). It contains 32 asanas, details for building body strength, 25 mudras to perfect body steadiness, 5 means to pratyahara, lessons on proper nutrition and lifestyle, 10 types of breathing exercises, 3 stages of meditation and 6 types of samadhi

- Shiva Samhita - author is unknown. This is yoga manual depicts an interaction between Shiva and his consort, Parvati. It talks about yoga, having a guru, asana, mudra, and siddhis

- Yoga Upanishads - Out of the 108 Upanishads, 20 are Yoga Upanishads. These are considered minor in ranking compared to the 13 major Upanishads. Yoga Upanishads discuss different aspects and kinds of Yoga, ranging from postures, breathing exercises, meditation (dhyana), sound (nada), tantra (kundalini anatomy). Some of these topics are not covered in the Bhagavad Gita or Patanjali's Yogasutras.

- Yoga Korunta (Kuranta) - only Krishnamacharya saw this before it was forever lost when it was devoured by ants. It was one of his guru dakshina - to find the Yoga Korunta, which he finally sourced at the University of Calcutta, as authored by the Yogi Korantaka

- Yoga Taravali - discusses yogic practices such as bandhas and advanced spiritual experiences like Samadhi

- Goraksha Samhita - by Yogi Gorakhnath

- Hatha Ratnavali - written by Srinivasabhatta Mahayogindra

Personalized Yoga

A teacher must always ask himself if what he is teaching is appropriate to the student. Ideally, the one-on-one class should be tailor-fitted to the student - his flexibility, strength, balance, intention, level, age, fitness, etc. Is she fat? lean? pregnant? Krishnamacharya says yoga should be adjusted according to a person's stage in life:

- srishti krama - for the brahmachari (young and strong, teen-ager) to push the limits and generate strength

- sthiti krama - for the householder, middle-aged, around 45. Energy is diminished, cell repair is not optimized, and stamina is shortened. Yoga at this point should be in maintenance mode - not going all-out for strength

- anta or samhara krama - for the sannyasi (monk or renunciate, people in their 70s), strength, stamina, and repair are all on the decline. The person has seen life and has maturity and equanimity. Yoga should be more meditative with breathwork - more spiritual

Bottom line is to know the body's limit and never traverse it - always stay on the edge. A good guide is to be able to hold an asana for a good length of time while breathing properly. If there is strain, it could be too much or too advanced.

Purpose / Implementation of the Practice

Sometimes, the student may not have a clear purpose for the practice. Sometimes, what he wants is not really what he needs.

Aside from purpose, it is essential to know the student. Two people having the same objectives in yoga can be prescribed different practices based on age, fitness level, level of motivation, occupation, time for the practice, beliefs, etc.

Yoga is practiced mainly for 3 reasons:

- Fitness - if the student wants to be fit, strong and healthy. Fitness can be focused on strength, flexibility, balance or stamina.

A child for fitness yoga entails lots of fast movement, jumping and somewhat playful. But an elderly man for yoga fitness will do slower movements, hold the movement for a few breaths and be meditative with synchronicity of breath and movement. - Therapy - yoga can be done to cure an illness or cleanse the system.

A child for therapeutic yoga for asthma could include training to a shoulder stand in a month. An elderly sedentary woman for the same purpose will have to undergo a longer period before a shoulder stand or risk structural damage. - Spirituality - on a quest to evolve and attain enlightenment mostly through meditation and pranayama.

A child for transformative yoga may do chanting to plant seeds for a deeper practice. An adult may do more pranayama and meditation and mantra chanting.

Spreading Yoga

Krishnamacharya was interested in a few worldly goals. One of them was to spread the practice of yoga, which he interestingly called propaganda.

IV Convincing Commitment (1973–1978)

Personal Mantra Initiation

Mohan and Krishnamacharya's relationship became close over the years. Krishnamacharya gave Mohan some studio pictures and gradually began to ask Mohan to do trivial things for the master. Krishnamacharya also began to address Mohan informally. After practicing with Krishnamacharya for 5 years, rarely missing a class and prioritizing the class over other endeavours, Mohan finally mustered enough sinew to ask Krishnamacharya to initiate him to a personal mantra. This is serious. When I guru does this, he takes ownership of the student's spiritual growth and acknowledges his role as guru to his student.

A ritual was performed and Mohan was given his chanting beads (japa mala) and his personal mantra whispered to him. He was to chant the mantra 108 times a day for the rest of his life.

V Pranayama, Kriyas, Yoga Therapy

Pranayama

Krishnamacharya, at age 100 can chant OM for a full minute. Pranayama stills the mind, strengthens the body and lengthens the life span. Pranayama can attain samadhi, and Krishnamacharya claims that it's the most important of the 8 limbs. Awareness has to be done with breath (not mechanical breathing), ensuring the breathing is steady and not fragmented. In Pranayama, many things come into play - mental awareness, deep long smooth breathing, and a steady body (movement can be disruptive). Ancient texts link pranayama not only to the mind but also to chakras, kundalini, kriyas, mantras, bandhas, dharana, therapy, doshas, asana, pratyahara, rituals, nadanusandhana,

and mudras.

Heartbeat

In 1930, at the behest of the Maharaja of Mysore, with physicians monitoring Krishnamacharya's heartbeat, he stopped it for a full minute. He did it again in 1970. Krishnamacharya claims that it happened naturally after years of pranayama (nadi shodhan) and meditation. By controlling his breath, he could control his heartbeat.

Chakras

Krishnamacharya, in his book, Yoga Makaranda, talks about awakening consciousness of the chakras. At first read of that book, I thought he meant being aware of the chakras - but what he meant was awakening the consciousness within the chakras themselves - through pranayama. Hatha Yoga Pradipika also talks about this in greater detail in the 4th chapter. Krishnamacharya, after some persuasion from Mohan, finally agreed to teach it because, "When I'm gone, no one can teach you this." Krishnamacharya stresses that the key to pranayama especially kumbhaka (breath hold), is to do it gently and gradually build proficiency. When rushed and done with reckless abandon, it can kill.

If kumbhaka (breath retention) is done on the inhale, one can experience chest pain and heart failure (note: I find this conflicting with Krishnamacharya's other texts, where he said overweight people should do antara kumbaka while lean people should do bahya kumbhaka - it implies that breath-hold on the inhalation is part of the practice. Furthermore, he mentioned in some text that when holding the breath after the inhale, we should feel the pressure within the body dissipate as prana finds its way throughout the body all the way to the tips of the fingers, toes and hair. Another instance of antara kumbhaka is the Tibetan Tantra practice of Tummo where vase-breathing consists of holding the breath after the inhale and then visualizing the short a syllable generating heat until it engulfs itself in searing heat.).

According to Krishnamacharya

- Pranayama (full breath cycle) depends on your fitness and age. The following applies only to healthy people.

At 30 years old (and a yoga teacher), pranayama should be half the asana time, so a 1-hour asana should have a 30-min pranayama.

At 40 years old, one must do pranayama 4X age, so 160 full pranayama breathing per day.

At 60 years old, Krishnamacharya said pranayama should be twice the asana time - so a 1-hour asana should be followed by 2 hours of pranayama - Kriyas - there are 6 major techniques to cleanse the body. However, Krishnamacharya feels that they are not necessary if you are proficient in asana and pranayama. Kriyas are a preparation for pranayama, not a therapeutic intervention. Only fat people and those with excessive kaphas (weight gain, fluid retention, allergies, excessive sleep, asthma, diabetes, and depression.) need the cleansing kriyas.

- Tantric Sex Practices - Krishnamacharya wasn't a big fan of this practice. He saw them as unnecessary and unsound. His guru discouraged it and asked Krishnamacharya not to teach it to his students. Even Mohan wasn't taught this, despite his request. (note: in Tibetan yoga, Tantra practice includes consort practice [sex with a partner] as part of the Short Path [the fastest route to enlightenment])

- Accepting Students - Krishnamacharya was particular in accepting students. He had to be sure about the students' commitment and resolve otherwise, his time would be wasted. Worse, if the student will not practice, yoga will not work, and the student will tell others that his teacher's yoga does not work. (note: this is actually a lesson for me. I'm usually over-enthusiastic in 'fixing' someone else's malady that I would go ahead and initiate even if the person showed little or no interest. I was even accused at one time that it was all about my ego. So much for charity. Now, I no longer give free classes. I restraint myself from giving counsel. If they want it, they should pay for it - that seems the only way they'll put value in what I'm doing for them. 'Free' never worked.)

- What Not to Teach - Krishnamacharya makes a decision if he will teach the student what the student wants to learn. The question he asks is, "What's the relevance of this to the student? Will this knowledge be useful?" If he decides that only parts of the subject is useful, he will only teach that portion. In short, he is judicious in what he teaches - not always the entire lot, stock and barrel. When Mohan asked Krishnamacharya to teach him non-attachment, Krishnamacharya refused. When asked, Krishnamacharya said that Mohan might think non-attachment meant he can leave his wife and kids to pursue spirituality as a monk. At that point in Mohan's life, he didn't need to waste his time learning such things. (note: this is important for me to understand this. Sometimes, I teach an entire subject matter simply because I know it, even though some parts may not be interesting or relevant to the student.)

- No compromise - Krishnamacharya would rather decline a teaching job if management set down rules unacceptable to Krishnamacharya. (note: I've done the same thing. Declining to teach because the studio wanted to play music, declining to teach because what the student wanted was something many yoga teachers could also teach [I would rather teach the yoga that's is unique to me and unique to the student's needs])

Yoga Therapy

Krishnamacharya says that there is no one asana for every disease, but a combination of diet, lifestyle, asana and pranayama. The approach has to be holistic. But the therapy could be esoteric and not intuitive. There was a patient to whom he recommended sitali with left nostril exhalation - I've never read that in any book!

VI Growing Closer (1978–1984)

Being Fulltime

Mohan, realizing he was in the presence of a great yoga teacher but couldn't squeeze in enough time to learn due to his engineering job, decided to quit his job and be a full-time yoga student of Krishnamacharya and a full-time yoga teacher as well. Yoga was not a well-paying job at that time (and even now), so he struggled to make both ends meet to support his wife and growing daughter.

Long Term Courses

Krishnamacharya would teach one-on-one. when a student requests to learn Hatha Yoga Pradipika, he would schedule an hour/week every week for the next 2 years or so until the course is finished. For both teacher and student, it's a commitment. Krishnamacharya particularly has a solid unwavering steadfastness about his commitments - in his 80s already, he would hardly ever cancel a class.

Failed Attempt to Standardize Yoga

In 1933, many new flavors and opinions about yoga were propagating from different established gurus at the time - Paramahamsa Yogananda, Kuvalayanand, and Yogindra. It was creating inconsistencies and confusion. Krishnamacharya arranged a meeting with all of them to unify yoga into one standard. Nothing came out of it.

A Typical Day for Krishnamacharya

Krishnamacharya was set about his daily routine - starting the day at 2 am to do his asana-pranayama-meditation-puja (worship), Vedic rituals. He would practice again during lunchtime and practice again in the evening. In between, he would be teaching classes the entire day. He was an extraordinary yoga practitioner, a masterful teacher, and a spiritual adept.

Mastery of Mind

It is surprising to note that even though teaching yoga was Krishnamacharya's primary source of income, neither money nor changing his students were his priority. His deepening practice was all about mastery of his mind.

Hip Fracture

In 1984 (age 95), Krishnamacharya broke his hips. The doctor was fascinated to see Krishnamacharya's pulse beat like a hammer...like a man 30 years younger. Krishnamacharya refused the surgery and lived with limited mobility for the next 6 years until he died.

VII The Mind: Yamas, Niyamas, Meditation, and Related Practices

Yoga Yajnavalkya

Yoga Yajnavalkya is an ancient Hindu yoga text similar to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, with the addition of the kundalini and a deep discussion about pranayama, pratyahara, dharana and dhyana. The format is a male-female dialogue between the sages Yajnavalkya and Gargi.

Below are lessons from the Yoga Yajnavalkya, as taught by Krishnamacharya to Mohan.

Alms Round

A monk has to beg food through several houses in a village and not favor one. He can only eat one meal a day. A more extreme monk will only stay in the forest and wait if anyone will come to bring him food, or go hungry.

Ahimsa (non-harmfulness)

inflicting no harm or suffering by thought, deeds or words - for as long as practical. Purity of intention is the best measure of progress - thus you cannot be clever with your deeds. Everything else in yoga is subordinated to ahimsa - anything that harms is not yogic (granting that it is not entirely possible...you walk the woods and you step on small insects).

Charity and Compassion

Krishnamacharya, a man of austerity who has no money to spend freely, would never bargain the rate of a rickshaw man. According to him, you never deprive a less fortunate to his means of livelihood. (note: I've seen the Thai people take this even a little further. They would buy something a vendor might sell even though they won't have use for it. They would then just give it away to their friends. Their volition is to simply support the vendor. You can gauge the character of a people by what is in their culture, tradition and practices. Thai people are special that way)

Truth

Truth is not only telling what it is or conveying a fact. Truth in yogic tradition should not harm. Gossiping, even if true, harms the victim and thus not yogic. Thus between truth and non-harmfulness, truth is subordinated - everything else in yoga is subordinated to ahimsa.

So, what is truthfulness? Staying truthful frees us from the temptation of saying false things - exaggeration, half-truths, biased truths, and everything else our clever minds conjure to further our egotistical agenda.

Silence is a good practice. You speak less and you tend to be concise and clear about what you say when you speak less. A silent meditation retreat can be helpful and/or designate an hour a day to be silent. But don't let the mind wander away during silence - the purpose is defeated. Make it meditative.

Do Not Covet

Don't take what is not yours. It's simple, but it can carry over to less obvious practices. When you use other people's knowledge, do you give them due credit? Do you take other people's time by unnecessarily using them up?

Celibacy

(note: I do not agree with the yogic tradition of sexual restrain. Why create a dam to stem natural human behavior? Since sex is part of existence, then use sex as a means to leverage into the path - the way tantric yoga does.)

Be Content, Do Not Over Acquire

Krishnamacharya would say, "What is the point of accumulating money beyond a point?". He was never rich and never pursued wealth. It was more important to him not to have enemies, not to be in debt and sleep well at night. Acquiring wealth, maintaining a declining wealth, protecting wealth, all lead to unhappiness. (note: in this blog, I often talk about the 'burden of ownership'. To have nothing, but have enough to survive, gives the most freedom, contrary to instinctive needs and wants. I don't feel the need to protect something, then no need to worry about what you leave behind, and you can turn your life on a dime as you see fit. I may not have money, but my politics are mine, I am free to choose my divinity and I am beholden to no one. My ability to say NO is not compromised. I have refused my inheritance and my possession is only what fits into my backpack. This is freedom.)

Vidya (Knowledge)

An ancient Sanskrit saying goes:

"A fool is respected in his house. A man is respected in his village. A king is respected in his lands. A knowledgeable person is respected everywhere."

Krishnamacharya's devotion to his practice is equaled only by his thirst for knowledge. He would voraciously read volumes of books not just on yoga but on many subjects. He is quoted, "a man in search of knowledge cannot rest or sleep until he is satiated...knowledge must be applied otherwise it's useless information". (note: I feel strongly about the quest for knowledge. When someone is always thirsty for knowledge, he never gets old...life is always fresh and full of wonders. I also see knowledge as the building block of wisdom. When different knowledge is woven together for application, wisdom emerges.)

Tapas (Austerities) / Mitahara (Controlled Diet)

For longevity, one must eat less. This is also stressed by longevity expert David Sinclair when he said the secret to a long life is 'eat less often'. Krishnamacharya calls fat, the 'bad flesh' and encourages the practice of asanas (and to limit eating) to melt the fat. A lean and supple body induces the flow of prana and circulation of blood. Early death is caused by a bloated belly - nothing else. To melt the belly fat, one should practice janu sirsasana.

Krishnamacharya's 4-Step approach to conquer obesity:

- eat less and eat less often

- practice asana and pranayama

- fast or skip a meal

- strong determination to give up the food entirely

A fat body will cause short and erratic breathing - proper pranayama and bandhas are not possible. Without pranayama, long life is not possible.

A yoga adept should have the following qualities:

- slimness of the body

- brightness in the face

- manifestation of the nada (inner sound)

- very clear eyes

- freedom from disease

- control over the seminal fluid

- stimulation of the digestive fire

- complete purification of the nadis

Chanting and Mantras

From age 5 to his death (101), Krishnamacharya has been faithfully chanting the Vedas from memory. Mantra meditation has deepened his yoga practice and the other way around as well. Vedic chanting has been an oral tradition committed to memory from teacher to student (it wasn't written down). The chanting is precise - in pronunciation, pitch, speed, etc. Krishnamacharya was an uncompromising teacher - no deviation would go unnoticed. Whenever Mohan made a mistake, Krishnamacharya would stop immediately and make the correction. Mohan was able to record Krishnamacharya in his Vedic chanting and this recording survives to this day (but I couldn't find it on Youtube).

Devotion and Rituals

Devotion is optional in the practice of yoga, but its importance is made clear in the Yoga Sutras. If there is such a thing as a shortcut in the sutras, it is not kundalini arousal or any other esoteric practice. It is devotion to the divine.

Krishnamacharya was again uncompromising about his Vaishnavite devotion with his yoga practice - they are tethered or even 2 sides of one coin (yoga and devotion). However, he is very clear that devotion and yoga are two different things. He even walked away from a paid radio program because he will not agree to remove his devotional chanting before and after the program. He claimed that the studio wasn't providing for his needs - that his god provides for his needs.

When asked how he could get good sleep at an old age, he answered, "I have surrendered my burdens to the Divine, and he will take care of me. Why should I not have peaceful sleep?" As Krishnamacharya tries to fall asleep, he chants a mantra in his mind while thinking his head is cradled at the feet of the divine.

Pratyahara (Control over the Senses)

Controlling what we perceive with our senses enables the mind to remain focused - less distraction that pulls the mind away, the better. Do we need to see porn? Do we need to hear gossip? Do we need to get drunk?

When there is no control over the senses, the mind gets restless and boredom sets in. When you get bored, it is a red flag that we need greater control of our senses. The greatest temptation for losing control is food and sex. This issue is to be managed first for the mind to be steady.

Instead of struggling with the senses to gain control, it is best to do pranayama instead. The focus automatically reverts inward. As often said in yoga, "take refuge in the breath".

Touching other people leaves an imprint in the mind. It is best not to touch anyone unless needed.

Dharana, Dhyana, Samadhi (Meditation)

These 3 are progressively deeper stages of meditation. Dharana (a state of mental concentration on an object without wavering) is not possible unless pranayama and pratyahara are already established. When a person is in samadhi, the outside world cannot disturb him (note: A good example of this is Ramana Maharshi. He was in samadhi for 3 years, not knowing that his body was already being devoured by insects).

Consciousness resides in the heart (not in the head). To know this, the mind has to be steady, focused and without movement.

Krishnamacharya laments that in modern times (1980s), so many ancient yoga practices and traditional knowledge have been lost. It's now asana-centric and putting focus on the steadiness of the mind is no longer practiced. (note: I begin to wonder now, in 2022, how much more have been lost? What exactly are the practices in ancient times? And the sacred texts of yoga are still around [Patangali's sutras, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, etc.], so what exactly did Krishnamacharya mean when he says traditional knowledge has been lost?).

It is good validation if the meditation thoughts in the waking times become the dream as well.

VIII Last Years (1984–1989)

A Widower

Krishnamacharya's wife died a year after his accident. He had to move down the ground floor where he stayed until he passed on. He became dependent on other people since the accident. He could no longer walk to the market, no standing asanas, nor perform his puja (worship). A man of weaker constitution would have fallen into depression, but Krishnamacharya remained mentally steady and solid as a rock. Already in his 90s, his recall remained impeccable - still recited sutras from memory and remained sharp.

Non-Attachment

When asked what the litmus test is for an accomplished yogi, Krishnamacharya remarked 'non-attachment' - from relatives, family, loved ones and everyone else.

100 Years Old

Mohan organized the 100th birthday celebration of Krishnamacharya (he acquiesced reluctantly). Yoga pundits and a tv crew were there. 3 yoga graduates were presented their diplomas.

Krishnamacharya was a spiritual adept with rare mastery. Yoga and all the other rituals were his means to master his mind. His quest for knowledge and ability to learn earned him 6 degrees in Vedic philosophy - unmatched during his time. All his life, he pursued learning. He was the perfect embodiment of his teachings. To him, it wasn't about earning the degrees but applying knowledge in his day-to-day life. Krishnamacharya had good teachers with great merit, but none did what he did - climb up the Himalayas to live with a brahmachari guru for 7 years in pursuit of deeper yoga. His devotion to the divine was his cornerstone. All his life, he was devoted to his deities. It is unfortunate that he did not live long enough to see the millions around the world who now practice the yoga he taught.

When asked by Mohan shortly before Krishnamacharya passed away, which was most important in life, Krishnamacharya said, "It's not money. Health, longevity and a tranquil mind."

IX Works of Krishnamacharya

Classification of Works by Krishnamacharya

Over six decades, from the 1930s to the 1980s, Krishnamacharya authored four books on yoga, several essays, and some poetic compositions. The essays and compositions were short, ranging from two to ten pages.

Other works (essays and poetic compositions) are below. First 17 items listed are works on yoga or are closely related to yoga.

- Yogaanjalisaaram

- Disciplines of Yoga

- Effect of Yoga Practice

- Importance of Food and Yoga in Maintaining Health

- Verses on Methods of Yoga Practice

- Essay on Asana and Pranayama

- Madhumeha (Diabetes)

- Why Yoga as a Therapy Is Not Rising

- Bhagavad Gita as a Health Science

- Ayurveda and Yoga: An Introduction

- Questions and Answers on Yoga (with students in July 1973)

- Yoga: The Best Way to Remove Laziness

- Dhyana (Meditation) in Verses

- What Is a Sutra?

- Kundalini: Essay on What Kundalini Is and Kundalini Arousal (sakti calana) Based on Texts Like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Gheranda Samhita, and Yoga Yajnavalkya

- Extracts from Raja Yoga Ratnakara

- Need for a Teacher

- Satvika Marga ("The Sattvic Way"; philosophy/spiritual/yoga)

- Reference in Vedas to Support Vedic Chanting for Women

- Fourteen Important Dharmas (philosophy)

- Cit Acit Tatva Mimamsa (philosophy)

- Sandhya-saaram (ritual)

- Catushloki (four verses on Sankaracharya)

- Kumbhakonam Address (catalog)

- Sixteen Samskaras (rituals)

- Mantra Padartha Tatva Nirnaya (rituals)

- Ahnika Bhaskaram (rituals)

- Shastreeya Yajnam (rituals)

- Vivaaha (marriage rituals)

- Asparsha Pariharam (rituals)

- Videsavaasi Upakarma Nirnaya (rituals)

- Sudarshana Dundubhi (devotional)

- Bhagavat Prasadam (devotional)

- Narayana Paratva (devotional)

- About Madras (miscellaneous)

Works on Vedic Rituals

Krishnamacharya wrote about Vedic rituals many decades before when it was still widely practiced. It has increasingly lost popularity in modern times due to its impracticality. Even Krishnamacharya himself refrained selectively from teaching them due to its declining relevance.

Devotional Works and Compositions

Krishnamacharya was deeply rooted in his devotional tradition, Vaishnavism, with its deity, Narayana (an emanation of Vishnu).

When Krishnamacharya's wife died, he was heard by Mohan to be chanting, "Narayana...Narayana...Narayana...Narayana..."

Philosophical Works

Krishnamacharya's work on Vaishnavism literature and philosophy is technical and assumes a background in the discipline. He didn't write anything new from tradition, but simply expounded to deepen a reader's understanding and appreciation.

Short works on Yoga

Krishnamacharya's short essays on yoga are vastly overshadowed by his teachings in classes, lectures and presentations. In short, his essays are not as comprehensive to convey his knowledge and experience. He didn't write them with the intention of getting published.

Books on Yoga

- Yoga Makaranda - Krishnamacharya wrote this book in only 3 days, back in 1934, at the behest of the Maharaja of Mysore. He lists 27 references in writing this book, including standard yoga texts like Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Yoga Upanishads, Gheranda Samhita, etc. This book expounds and embellishes the benefits of yoga. (note: This is the master's major book, but it has not become the bible of yoga. Perhaps it's because it is a hard read. It could have benefitted from further refinements by a professional editor). Aside from the 42 asanas, it talks about nadis, chakras, prana, mudras, and bandhas.

- Yogavalli - this book is Krishnamacharya’s commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, which was dictated from memory for over 4 years when he was in his 90s. Yogavalli's philosophical interpretation however, has a heavy lean on Vaishnavism, Krishnamacharya's devotional tradition, with Vishnu as its divine deity. But the fundamental principles of the sutras (8 limbs) remain unchanged - just the philosophical interpretations.

- Yoga Rahasya - this book is credited to the Vaishnavite saint, Nathamuni, who comes from Krishnamacharya's lineage. The story goes that at 16 years old, Krishnamacharya visited the birthplace of Vaishnavism's earliest saints and then fell into a meditative trance. When he came out of it, he claims that the lost work of that saint was transmitted to him by Nathamuni. At any rate, this book is unorganized and could have been refined to make it coherent and continuous.

- Yogasanagalu - a practice manual for a variety of asanas. However, Krishnamacharya's student of 33 years, Srivatsa Ramaswami, wrote extensively about these asanas in his book, The Complete Book Of Vinyasa Yoga

Appendix I: Book Excerpts and Summary

YOGA MAKARANDA

8 Limbs of Yoga

The essence of yoga is to withdraw the mind from all external activities, draw it inward, and keep it contained within. Yoga yields great benefit only after some time when practiced systematically [krama]. The benefits are not instantaneous.

The benefit of yoga comes from what you practice from the 8 limbs:

- Yama & Niyama - compassion towards all living beings arises. One will have universal compassion towards all living beings and develop internal purity. Personal peace and order in society will arise.

- Asana - gives us strength

- Pranayama - gives us health and longevity, strength of prana, mind, intellect, and speech. The unsteady nature of the mind is arrested. It purifies the blood, and the blood flow leads to proper functioning of the nadis and chakras. Pranayama should be done with mastery over the yamas, niyamas and asana - otherwise it will not deliver the wanted benefits.

- Pratyahara - to control the senses and not to allow them to wander as they wish

- Dharana - to hold the mind at an appropriate object (also called samata). This is the way to ekagra-citta [one-pointed state of mind]. Control over the mind will lead to control of all the senses. Anything that one wishes will come true, like the blessings and curses of ancient sages. Of the 64 vidyas (right knowledge or clarity), only yoga gives directly observable [pratyaksha] results.

Yoga Nidra

The steadiness of mind brought about by yoga is a thousand times more beneficial than that brought about by regular sleep. This is yoga nidra. In fact, all of our time is wasted until we attain such steadiness of mind through yoga. (note: I have read on numerous texts that adept yogis no longer sleep - they just do yoga nidra).

Practice, Intellectualizing and Detachment

In yoga, jnana [knowledge, enlightenment] is not enough. Without the actual practice, it is nothing more than intellectual adventurism. And about practice, yoga yields more benefits with the practice of yama and niyama (right conduct for self and others) rather than tapas (austerities). Yoga can be practiced by everyone except the lazy and those who do not want changes in their lives. Detachment has to be practiced with yoga, especially when siddhis arise. One who succumbs to the power of their siddhis becomes a slave to it and loses their practice (the applause feeds on the ego)

Body, Mind and Self

The body is gross the mind is subtle. The mind is constantly changing by nature, making it difficult to appreciate the nature of our mind. The Self (Atma, consciousness) is the nature of consciousness and the source of all knowing. (note: at the end of the day, the only thing that has an objective existence is the self [atma, consciousness] - everything else is an illusion and perception). All 3 are connected. When the body is healthy and calm, the mind becomes steady and calm as well. When the mind is steady, the Self is revealed. When the body is nourished by healthy food, the body becomes strong and the mind remains optimized and functional and the Self remains in the body. Without food, the body dies and the mind dies with it, and the Self moves to another body. This is an example of their interconnectedness. The Self is unchanging. It doesn't die and it doesn't get reborn. It moves from life to life, body to body as life leaves the body. It is what reincarnates. Desire causes the Self to be reborn. Without desire, the rebirth no longer serves a purpose.

Prana

Without prana, we die - that is how important it is. The important role it plays begs that prana must be purified and put under our control. We can control prana through breath regulation known as pranayama.

Asana

There are many claims to how many asanas there are - from 8.4 million (the number of varieties of living things) to 84 (a popular number in some centers). Krishnamacharya knows 700 while his guru, Ramamohana Brahmachari knows of 7,000. Regardless of the number, the following should be adhered to in the practice of asana:

- Drshti - the eye gaze should be on the Ajna Chakra if not specified (note: personally, I'd rather close my eyes and internalize the body sensation and the flow of breath)

- Jalandhara bandha - whenever possible, when the asana position is established, chin to the chest to lock the energy

- Symmetry - practice on both sides, first to the right and then to the left, otherwise the benefit of yoga will not spread to all parts of the body

YOGA RAHASYA

This is a difficult book to follow because it doesn't flow and not the most coherent. It talks about the same topics already covered, but it paid attention to yoga for women and the essential role they play in society. It presented yoga for pregnant women - asanas that are appropriate and not.

It also touched on appropriate yoga for the monk, the householder and the celibate.

Ending Thoughts

After Veer, I've always been in search of a teacher...that was 8 years ago, and I am still searching. I've met many competent yoga teachers whose classes I've thoroughly enjoyed. But not someone I can consider my mentor and teacher.

The one yogi who fascinated me more than any other is Krishnamacharya. I've devoured everything I could about him. I am consumed by his life, his teachings, his discipline, and his legacy. Through his books (Yoga Makaranda, Yoga Rahasya), through the writings of his direct students (AG Mohan, B. K. S. Iyengar and Srivatsa Ramaswami), and downline lineage (David Svenson), I get a glimpse of this magnificent life. As I internalize the way he lived his life, and as I codified his teachings into a practice, I realized my search for a teacher is over. I have already found him long before I realized I did.

In humility, I bow down to my great teacher, Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. I am grateful for all his teachings, as I am grateful to all his students who have propagated his teachings.

--- Gigit (TheLoneRider)

YOGA by Gigit ![]() |

Learn English

|

Learn English ![]() |

Travel like a Nomad

|

Travel like a Nomad ![]() |

Donation Bank

|

Donation Bank ![]()

Next Peoplescape/Story:

![]()

![]()

Yama (1): Eight Limbs of Yoga

(May 1, 2022) In Patangali's Yoga Sutras, he codified yoga into 8 branches in priority sequence - the first of which is Yama or one's moral conduct to harmonize oneself with society. This is the foundational cornerstone for the practice of yoga.....more »»

![]()

![]()

![]()

Magic and Mystery in Tibet

by Alexandra David-Neel

(Jun 12, 2022) This semi-biographical Buddhist/adventure book is an account of Alexandra David-Neel's sojourn in the hinterlands of Tibet back in 1924 when it was virtually unknown, obscure, unwelcoming and shrouded in mystery.....more »»

Chiang Mai INFORMATION

Chiang Mai Map

Chiang Mai, Thailand

Chiang Mai FYI / Tips

- crop-burning season in Chiang Mai is between late Feb to early April. But laws change everytime. This year, 2019, there is a 61-day ban on burning so the farmers started burning early. When my plane was approaching Chiang Mai on Jan 24, 2019, there was already a thick blanket of smog covering the entire city (and beyond). But within the city itself, you won't feel it (but that doesn't mean the air is healthy). To monitor air conditions in real time, refer to site: Chiang Mai Air Pollution: Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI)

- hot season begins March and lasts until June

- wet season begins July and lasts until September

- best time to visit Chiang Mai is mid-September to mid-February - after the monsoon and before the burning

- you have to try Khao Soi, this is north Thailand's culinary staple

- the tourist area where most of the hotels, restaurants, ticket offices, tour operators are, is located in the Old City

- to exchange your dollars to Thai Baht, the Super Rich Money Exchange give the best rates. There are many branches scattered around Chiang Mai

- get a red cab (songthao) outside the train station for Baht 50 (instead of paying B100 if inside the train station) to Old City - if you haggle nicely enough...I did!

- shared red taxi (songthao) - B30 standard fare plying all over Old City

- for only B50/day, best to rent a bike to go around the Old City - it's a 2.5km2 with lots to discover

- FREE daily yoga classes from 9:00am to 10:15am at Nong Buak Hard Park (southwest corner of Old City). Resident and passing-through teachers take turns conducting yoga classes.

Blues/Jazz Bars in Chiang Mai

- North Gate Jazz Coop - at Chang Phueg Gate, great Tuesday jam session, Blues on Sundays at 11pm by the Chiang Mai Blues band

- Boy Blues Bar - at the Night Bazaar. Mondays at 9:30pm is open mic

- My Secret Cafe - near Wat Phra Singh. Tuesdays at 7:30pm for the changing front-act and 9:00pm for the Panic Band

- Taphae East - 88 Thapae Rd. (just north of Night Bazaar). Fridays at 9:30pm by Chiang Mai Blues Band

Chiang Mai Cost Index

- B60 Chiang beer

- B250 1 hour drop-in yoga session

- B200 one hour Thai body massage at WAYA Massage (highly recommended)

- B50 noodle soup with meat

- B50 coffee

- B40 pad thai

- B30/kilo wash-only laundry

- B50/kilo wash+iron laundry

- B100-150 dorm bed/night

- B250 fan room/night

- B30 internet cafe/hour

- B170-190 Movies Sat-Sun and public holidays

- B130-150 Movies weekdays

- B100 Movies Wednesdays (movie discount day)

- B750 1/2 day Thai cooking lessons

- B900-1000 1 full day Thai cooking lessons

- B400 Muay Thai boxing ticket

- B2500 starting room rate at the luxury hotel, Nawa Sheeva (highly recommended)

- B450 bus, Chiang Mai to Bangkok

- B160-180 bus, Chiang Mai to Pai

- B1250 bus, Chiang Mai to Luang Prabang

- B1650 slow boat, Chiang Mai to Luang Prabang

- B210 bus, Chiang Mai to Chiang Rai, 3-4 hours

- B360 Green VIP bus, Chiang Mai to Mae Sai (Thai border town for visa run to Tachileik, Myanmar)

- B50 bicycle rental, 24 hours

- B200 motorbike rental, 24 hours

- B273 #51 sleeping train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai

- B638 #7 a/c train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai

- B50 red taxi fare from point to point

- B100 red taxi fare from train terminal to city

- B2000 full day elephant sanctuary

- B750 Chiang Rai one-day tour

- B1500 mountain biking scenic ride

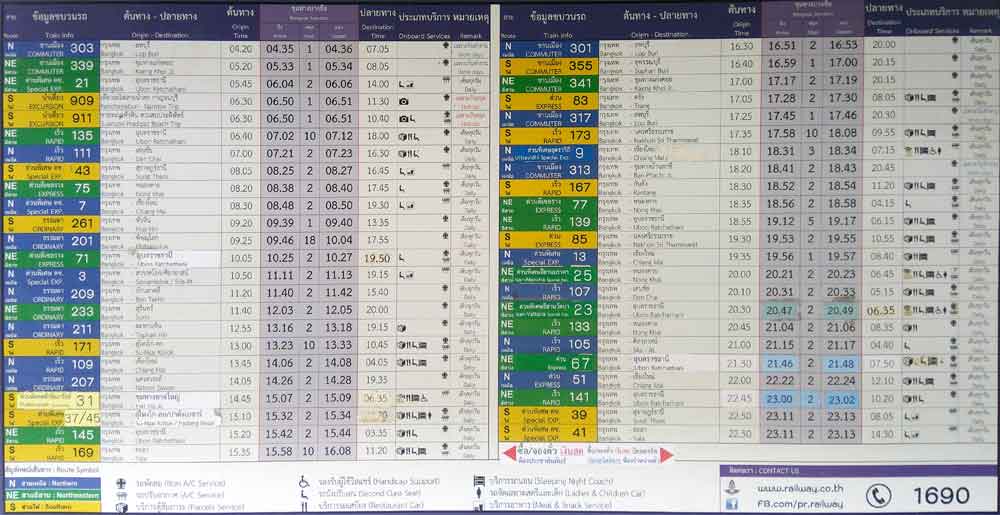

Chiang Mai Trains by Train36.com

- Chiang Mai trains for Bangkok - 2 day trains, 3 night trains, daily schedule

- Train 14 to Bangkok - departs 5pm daily, arrives BKK 6:15am, 1st class and 2nd class sleeping accomodation, Special Express

- Chiang Mai trains to other destinations -

Chiang Mai to Bangkok Trains

source: railway.co.th- Check Train Schedule & Fares

- Book Online - direct booking with State Railway of Thailand. Best to register first. If going to BKK from CNX, click "Northern Line".

note -- big difference between booking direct with the State Railway and booking with an online 3rd party agent. 12GO was charging B1330 for the same trip that only cost me B941 with the State Railway.

note -- Oct 2022, I took the #10 Train from CNX to BKK, upper berth, 2nd class, a/c, sleeper, B941. The train was clean, fast, comfortable and modern. If you have heavy luggage that will cost more money in flight checkin, I would suggest this train. Otherwise, the flight now is so much cheaper it doesn't even make sense to take the bus or train.

Bangkok to Chiang Mai by Train from Bang Sue Train Station

For more train info: Bangkok to Chiang Mai trains - departing from Hua Lamphong - MRT (Bangkok)

(I'm using Bang Sue as a starting point because I was closer to it, but you may be closer to the Hua Lamphong station)

- take the MRT train to Bang Sue Station. Take the #1 Exit to the north provincial trains

- Proceed to Counter 2. You will see an

information booth, a

train schedule chart and the

ticket counter. Choose the train and pay at the ticket counter.

- daily train schedule:

- 8:48am - #7 Train, arrive Chiang Mai 7:30pm, not sleeper, B638

- 2:06pm - #109 Train, arrive Chiang Mai 4:05am, sleeper

- 6:31pm - #9 Premium Train, arrive Chiang Mai 7:15am, sleeper, B938 upper deck, B1038 lower deck

- 7:56pm - #13 Train, arrive Chiang Mai 8:40am, sleeper, B768 upper deck, B838 lower deck

- 10:22pm - #51 Train, arrive Chiang Mai 12:10pm, sleeper, 3rd class B270 (non sleeper), 2nd class B438, B728 upper deck, B798 lower deck

Loei to Chiang Mai by Bus

- From Loei town center, take a tuk-tuk ride to the bus station, B30. There is only one bus station.

- As of June 28, 2020 (still on Covid schedule), there are only 3 night trips: 8:30pm, 9:30pm and 12 midnight. 9 hours, B470.

- The bus makes the following stops at the following times from a 9pm Loei departure: Phu Ruea (9:50pm), Phitsanulok (12:40am), Uttradit (2:20am), Lampang (4:35am)

- Final bus stop is at the Red Bus Arcade, Chiang Mai, 9 hour-trip, arriving 6am (from 9pm Loei departure).

- Take a red songthaew to Old City, B50. They'll try to charge you B100, but they'll take B50 (just assure the driver you won't tell the other passengers).

Chiangmai Blogs by TheLoneRider

- Goodbye Chiang Mai Jan 24, 2019 - Oct 10, 2022

- Chiang Mai Peoplescape Oct 10, 2022

- Siamaya Chocolates Oct 2, 2022 [an error occurred while processing this directive]

- September Snapshots Sep 30, 2022

- Carrot Cake Sep 12, 2022

- Making Coconut Bread Sep 3, 2022

- August Snapshots Aug 31, 2022

- Yoga Nidra with Chunyah and Tom Aug 18, 2022

- Coconut Pancake Aug 11, 2022

- July Snapshots Jul 31, 2022

- Chiang Mai Peoplescape Jul 31, 2022

- Jason, Max and Elizabeth Pizza Nite Jul 28, 2022

- Yakiniku Dinner with Max and Jason Jul 25, 2022

- Icebath at Nawa Saraan Jul 6 - Oct 5, 2022

- June Snapshots Jun 30, 2022

- Tom, Chunyah and Simona Pizza Nite Jun 23, 2022

- Yoga Class Pizza Nite Jun 15, 2022

- Pranayama with Nicha Jun 14, 2022

- May Snapshots May 31, 2022

- Lover's Quarrel May 26, 2022

- Getting Lost on a Hike May 25, 2022

- Biohacker Meetup at 'Living with The Spirit' May 22, 2022

- Music and Magic at Paapu House May 5, 2022